Founded in the 17th century, the city of Stratford, CT, boasts a beautiful landscape and a rich history. This is the birthplace of the American helicopter industry. Here, in 1939, a Russian immigrant, a young engineer by the name of Igor Sikorsky, tested his first helicopter and founded the first manufacturing plant on the outskirts of town. Later his name would gain world renown, and Sikorsky Aircraft would become an enormous helicopter-building empire, a supplier of aircraft for commercial and military purposes.

Today, as in the middle of the last century, a good half of the male Russian-speaking population of Stratford works at Sikorsky.

But outside of �Russian Stratford��few know that the famous aircraft builder, a graduate of the Kiev Polytechnical Institute, Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky, who gained renown for his planes named �Ilya Muromets� and �Russky Vityaz�� was a deeply religious man. Emigrating after the Revolution to the United States, he wrote and published a book on the Lord�s Prayer, and exerted a great deal of effort during the establishment of the first Orthodox parish in the city, St Nicholas Church, which on December 15, 2009, celebrated its 80th anniversary.

Today, Protopriest Theodore Shevzov serves at this church, one of the senior priests of the Russian diaspora, who knew the legendary inventor personally.

***

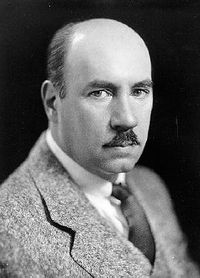

� Igor Sikorsky was a very humble man. Out of a lineup of, say, 15 men, Igor Ivanovich would probably be the least noticeable. Once, some Americans who didn�t recognize him, asked him what he does. He replied: �I work at Sikorsky.�

� Igor Sikorsky was a very humble man. Out of a lineup of, say, 15 men, Igor Ivanovich would probably be the least noticeable. Once, some Americans who didn�t recognize him, asked him what he does. He replied: �I work at Sikorsky.�

Sikorsky was not very talkative, he tended to listen rather than talk. But when asked, he would talk about himself and his experiences.

He was infected with the idea of helicopter flight at the beginning of the 20th century, in the early days of aviation. But everyone, including Americans, thought the idea unworthy of serious consideration, and preferred to concentrate their efforts not on helicopters but on airplanes.

But Sikorsky built a helicopter factory in Stratford�at the time a humble endeavor�and began to gather Russian workers. All of our male parishioners worked at Sikorsky, the biggest employer of the city at the time.

� St Nicholas Parish is closely bound to the Sikorsky name�

� The Parish was indeed founded thanks to the efforts of Igor Ivanovich. At the end of the 1920�s, a Russian community began to assemble around him in Stratford. On December 15, 1929, the parish was founded, and the construction on the Church of St Nicholas the Miracle-worker began on October 12, 1941.

At first, the parish would gather at a private house on Lake Street. Most of the parishioners were recent immigrants to America from Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, and by and large they were educated people. Almost all of them, including my father, Ivan Ivanovich Shevzov, considered themselves refugees. They did not believe that they were settling in America permanently, they dreamed and hoped that they would return to Russia sooner or later. Still, wherever they settled, the first thing they would do was establish a church.

Igor Ivanovich was not yet a leader, did not have a lot of money, but he did not refrain from helping to establish the church.

The first Rector of the parish, which was still meeting at the house, was Hieromonk Panteleimon (Nizhnik), who was helped by Fr Joseph (Kolos). Later they made their way to Jordanville, where a monastic community was established in 1930 in an open field, where they began to build a monastery. The construction of St Nicholas Church was finished in 1941, and the already-successful Sikorsky actively participated in its establishment. Most of the parishioners did not have big paychecks, of course, but they donated all they could to the community. Igor Ivanovich was a member of the parish until his death. He had his own �place� in the church, to the left of the altar, and he stood on that spot his entire life.

� Fr Theodor, were you already an altar boy then?

� Fr Theodor, were you already an altar boy then?

� Yes, I had a good deal of experience as an altar boy, some five or six years. As a child, I had served as an acolyte in church where Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) served.

Beginning in 1922, there were very many Russians there, most of whom had left Russia after the Revolution, thanks to Metropolitan Anthony and General Peter Wrangel.

We had a humble church, but everyone stood and prayed piously, no one spoke loudly [during service]. I already saw how one was to behave in the altar, how one was to act during service.

In 1948, after a brief stay in Germany, in a Displaced Persons camp, we came to America. I was 18 at the time.

After Fr Panteleimon left, Protopriest Stefan Antoniuk became the Rector between 1931 and 1969. I remember that he asked me to help him read on the kliros. I wanted to help, but I could not read Church Slavonic, and so he began teaching me. At the time I worked as a chemist, and I had no intention of becoming a priest, considering myself unworthy. I was what you would call an active parishioner. But in 1971, Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky) noticed me and ordained me a reader, and three years later made me a deacon. Only 14 years later, now-Metropolitan Hilarion ordained me to the priesthood. I served in Mahopac, in St John the Baptist Cathedral in Washington, DC, and at the same time worked as a chemical engineer.

I have been serving at St Nicholas Church in Stratford for six years, the same place where my church life in America began.

� Fr Theodore, your classical Russian language surprises not only Russian Americans, but Russians from Russia, and it is hard to believe that you were born in the monarchy of Yugoslavia, and that your first visit to your historic homeland, as is often written, was only in 2003. But this was a visit already as a priest. But your acquaintance with the Soviet nation occurred much earlier, is this not so?

� My ancestors are from the Buturlinovka region of Voronezh oblast. Yes, I visited Russia for the first time in 2003. My second trip was in 2007, and my third in 2008.

But the very first time I came to the USSR was at the end of the 1950s as a member of an American delegation of chemists. They had searched for an interpreter for this delegation for a while, but not a simple interpreter but specifically a chemist who did not only speak Russian but knew the specialized terminology.

Two old emigres who were offered the job refused to go to the USSR, where, in their words, �there was terror and it smelled of blood.�

And so in the listings of the American Chemical Society, the organizers of the trip noticed the name Theodor Shevzov, a young specialist in plastics in one of the largest chemical companies in the US. They offered me the job and I agreed.

We were invited by the Ministry of Chemical Industry. The nine-person delegation which included the presidents and vice presidents of leading chemical concerns stayed at Moscow�s Ukraina Hotel. At the time, I was very young, a �green� chemist. The Minister of Chemical Industry of the USSR, Tikhomirov, personally welcomed us.

For six weeks, we traveled to plants in Vladimir, Orekhovo-Zuevo, Leningrad, Tbilisi, and for less than a week in Moscow.

This busy schedule did not permit us to leave the group to go to church. Only in Vladimir, early in the morning we were able to attend a service in Uspensky Cathedral, which was celebrating its 850th anniversary at the time. The church was remarkable in scale. This was the most memorable impression of church life during that visit.

In Moscow, I managed to excuse myself, and instead of visiting an exhibition of chemical products, took a taxi to Staro-Konyushenny Lane, where my mother, Vera Mitrofanovna Pavlovskaya, was born, a niece of the composer Alexander Dmitrievich Kastalsky.

Time was limited, and I was only able to take a stroll on the street a half-century later, in 2007.

In 2003, we discovered that a cousin of mine lived in Voronezh, a Maria Stepanovna Shevzova, a teacher of Russian for 34 years. We started to correspond, and in 2007, I traveled to Voronezh. I was given the opportunity to serve in Resurrection Church, and I spent a great deal of time wandering the streets of my grandparents� city.

� Fr Theodore, you have been fortunate enough to know and serve together with renowned and revered people: clergymen, scholars, entrepreneurs, that is, with those who are part of Russian history abroad. Which of these gave you the most memorable life�s lesson?

� Fr Theodore, you have been fortunate enough to know and serve together with renowned and revered people: clergymen, scholars, entrepreneurs, that is, with those who are part of Russian history abroad. Which of these gave you the most memorable life�s lesson?

� I already talked about the remarkable humility of Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky. But I would also like to share one instructive anecdote, something that happened to me before I began my time as deacon.

This was in Mahopac, NY. The service, led by Metropolitan Philaret, was ending. Vladyka began to read a sermon. Then, Protodeacon Nikita Chakiroff came up to me and told me this story: Once, he was given the chance to serve with St John (Maximovich) in the very same church in Mahopac. The hierarch was reading a sermon. Everyone was already becoming restless, started talking� Fr Nikita also gave in to the general impatience and thought: �I wish Vladyka would hurry up and finish.� The hierarch then finished, turned to Fr Nikita and said �And you, Nikita, why do you think ill of me?�

�When you serve as a deacon,� Fr Nikita then instructed me, �never think of anything external, and do not under any circumstance think ill of anyone.�

This was one of the most noteworthy lessons I have ever learned.

Interviewed by Tatiana Veselkina, Stratford/New York.